When the movie "Memento" came out in 2000, audiences were stunned by the innovative storytelling. The film centered on a protagonist with no long-term memory — every few minutes, he’d forget what he just learned, and director Christopher Nolan allowed the story to unfold in reverse chronological order. The movie was more than entertaining — the unique format gave viewers an opportunity to piece together information the same way they would if they themselves couldn’t retain long-term memories, and it deepened the overall understanding of memory mechanisms in the brain.

"’Memento’ simulates what it feels like to be a person who has suffered damage to the hippocampus that has obliterated the formation of long-term memories," study author Iiro P. Jääskeläinen said in a statement. "Even short-term memories last only for a couple of minutes before they are gone. The hippocampus also gets damaged — albeit to a lesser extent — in cases of severe and protracted stress as stress hormones gnaw the brain."

Brain nerds (which honestly, probably should be all of us) will know that the amygdala plays a major role in controlling fear and the cerebellum makes coordinated movement possible. But how does the hippocampus work and why does it play such a pivotal role in keeping our memories safe?

What Is the Hippocampus?

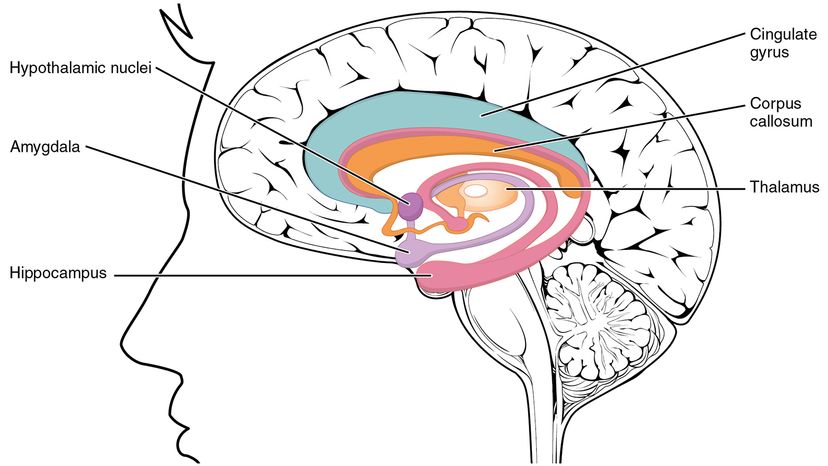

"It’s part of our limbic brain — a deep, primitive part of our brain that’s associated with emotion and memory," says New York City-based holistic psychiatrist, Ellen Vora, MD. "The hippocampus in particular is associated with consolidation of memory."

Located in the temporal lobe, the tiny horseshoe-shaped organ plays a massive role in the storage of long-term memories and the memory of the location of people and objects. Named for the Greek words hippo ("horse") and kampo ("monster") aka "seahorse," the curvy brain structure also resembles the small marine fish. As Vora explains, the hippocampus resides in the limbic system, which is associated with emotions and reactions. As you might expect, people who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease have demonstrated damage to the hippocampus.

What Does the Hippocampus Do?

The function of the hippocampus is perhaps most clear in examples of patients who’ve sustained damage to theirs. In the 1950s, scientists William Beecher Scoville and Brenda Milner described what happened to an epileptic man who’d received surgery on his hippocampus in an effort to relieve seizures: He retained memories from his childhood, but he couldn’t form new memories or piece together when or where things happened. That same decade, Dr. William Scoville began removing patients’ hippocampi (each person actually has one in each hemisphere, though both are generally referred to as "the hippocampus"). At the time, scientists knew it helped process emotions, but they weren’t totally clear on how. Scoville wanted to see what would happen if he removed the part of the brain in patients exhibiting certain symptoms like seizures. One such patient, referred to as H.M., underwent the surgery and found relief from his epilepsy but a near total loss of memory.

In the 1980s, Kent Cochrane (famously known in the psychology and neuroscience worlds as K.C.) fell off his motorcycle and lost several brain structures, including his hippocampus. Predictably, he lost most of his memories, but held onto some specific ones from his earlier life — all things that seemed rooted in fact and devoid of emotion or context. Experts later came to call these types of memories "semantic memories."

So while patients like K.C. could clearly keep a handful memories intact, most were lost. Now known as "episodic memory," recollections of personal experience are all pretty much a loss in the damage or removal of the hippocampus. K.C. for example, could remember that his brother had gotten married and he could recognize family members in photos from the day (all facts based in semantic memory), but he couldn’t remember his family reacting to the perm he got for the occasion (episodic memory).

Over time, scientists came to understand that the hippocampus is involved in two types of memory: declarative and spatial. Declarative memories are the ones associated with facts or events (semantic memory is considered one type of declarative memory; episodic is another type). The hippocampus is also involved in spatial relationship memories — the kind related to routes and pathways — and it’s also where short-term memories are turned into long-term memories, which are then stored elsewhere in the brain.

How the Hippocampus Can Sustain Damage

Different types of illness and accidents can damage the hippocampus (doctors generally aren’t removing hippocampi for experimentation anymore, like in the case of H.M.). Alzheimer’s disease is perhaps the most notorious destroyer of the hippocampus, as the illness has been correlated with atrophy (shrinking) of that area of the brain. As in the case of H.M, epilepsy is also known to affect the hippocampus — studies have shown that between 50 to 75 percent of epilepsy patients have hippocampus damage.

Two other serious threats to the hippocampus: severe depression and stress. In fact, studies have demonstrated that the hippocampus can shrink by up to 20 percent in people with severe depression, and reviews of studies found that people with severe depression may have hippocampi that are an average of 10 percent smaller than in those in people without depression.

"It’s a part of the brain that’s very susceptible to stress," Vora says. "We see it lose volume under conditions of chronic stress and depression. Conversely, you can restore your hippocampus with meditation and stress management. You want a healthy hippocampus so you can remember things!"

The Newest Research

A 2016 review of studies found that exercise in old age may have the ability to help strengthen the hippocampi’s ability to generate new cells, which could in turn help prevent cognitive decline. It’s still unclear how and why this works, but researchers are continuing to investigate the connection.

A 2017 study also found that the hippocampus may play a role in many more functions than memory and pathfinding — the tiny organ may also have a part in enhancing the responsiveness of vision, touch and hearing. Thanks to the continued new findings, some have begun referring to the hippocampus as "the heart of the brain."

Now That’s Interesting

Experts are pretty sure the human brain has always included a hippocampus, but the structure wasn’t discovered until 1564.