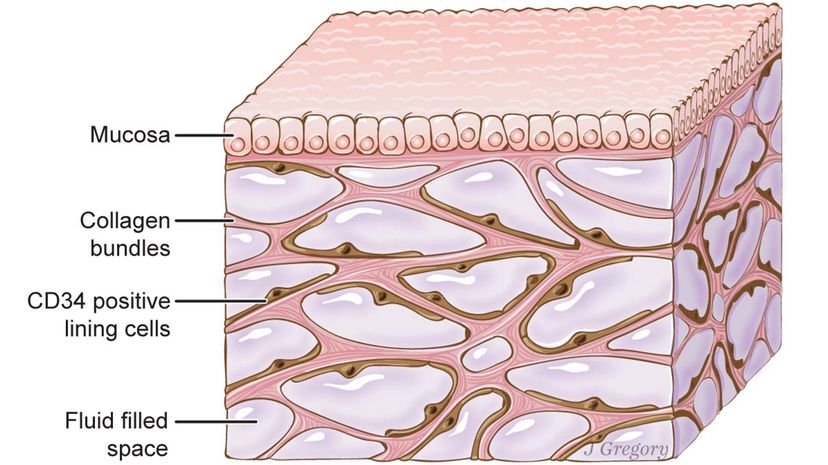

“Illustration of the fluid-filled web of collagen and elastin connective tissue, considered by some to be a new interstitial "organ." Illustration by Jill Gregory. Printed with permission from Mount Sinai Health System, licensed under CC-BY-ND.

“Illustration of the fluid-filled web of collagen and elastin connective tissue, considered by some to be a new interstitial "organ." Illustration by Jill Gregory. Printed with permission from Mount Sinai Health System, licensed under CC-BY-ND.

A discovery announced at the end of March 2018 may be seriously changing our understanding of human anatomy.

Researchers, including two doctors at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York, announced in an article published in Scientific Reports on March 27, 2018, that they had found a mesh-like network of tissue with cavities that allow fluid to move through the body on a previously unknown "highway." This web of tissue is found underneath the skin, surrounding blood vessels and lining the lungs, digestive organs and urinary system.

Previously thought to be simply dense connective tissue, the structure has now been identified as a fluid-filled web of collagen (a main protein found in skin and other connective tissue) and elastin connective tissue, and is being called a new organ by some of the researchers involved.

"It’s almost a highway for cells to move through tissue," says Rebecca G. Wells, a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and one of 11 authors of the report. This "highway" connects to the lymphatic system and could be a way cancer cells spread. "We have never understood the mechanism of how that happens," senior author of the report, Neil Thiese, told The New York Times.

If researchers gain a better understanding of the spread of cancer, they might be able to interrupt it, said Thiese, a liver pathologist at New York University School of Medicine.

A New York University press release said the discovery could add to our understanding of all organs and most major diseases.

How Was It Never Found Before?

In fact, doctors and scientists had often looked at this connective tissue, but did so by placing slices of it on slides under microscopes. In the process the tissue compressed and appeared solid, according to researchers.

But in 2014 Petros C. Benias and David L. Carr-Locke, clinical gastroenterologists at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Medical Center, were using a new imaging technique to look at a patient’s bile duct.

This high-tech endoscopy procedure "allows you to put a tiny tube into a bile duct and look down into the wall of the bile duct," Wells says. A fluorescent substance is used to help illuminate the tissues. "[The researchers] saw a lacy network-like pattern," she says. "They didn’t know what it was. They expected to see a solid barrier of collagen."

Neil Thiese was called in. "He had no idea what they were seeing either," Wells says.

But she says they "quite cleverly" took biopsies in 12 succeeding surgeries and froze the specimens to retain the water in the tissues. "It preserves the anatomy," Wells says.

Possible Insight into Alternative Therapies

Their investigation led some to describe the structure as a "new organ." Wells, herself, does not use the term, calling herself more conservative. However, the discovery "does suggest an unusual connection between different parts of the body," she says.

It also may help explain the reason some alternative therapies such as acupuncture and rolfing work. Acupuncture has been shown to be effective but we don’t know why, Wells says. Rolfing is a type of deep tissue massage that practitioners say improves health by restructuring the muscles and fascia, the tissue that binds muscles together.

A main function of the newly discovered network may be to serve as a shock absorber in the body, according to Wells. It’s strong and elastic and it surrounds skin, blood vessels and intestines. "These are tissues that are subject to mechanical forces," she says. A lot of movement occurs as the heart pumps blood, the lungs expand and digestion occurs, for example.

Wells says the discovery might also lead to a better understanding of fibrosis, the toughening and scarring of connective tissue often as a result of injury. The tissue network may also serve as a "third space" for fluid in the body. Doctors know that fluid collects in the spaces around cells, but these spaces are not enough to explain the swelling of tissues seen in some diseases, Wells says.

But, despite the headlines trumpeting a new organ, some scientists have a more muted response.

"It’s really cool," but it’s just one study, says Edward Pettus, assistant professor in the department of cell biology at Emory University. "It’s a different way of looking at interstitial tissue," he says. The tissue may be "different than we thought, but it’s not like we have a complete understanding of it."

"No one’s rewriting the textbook yet," he says.

Now That’s Interesting

"The last thing I needed was another organ," groused one commenter, when the Onion surveyed the public about the new discovery of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments found throughout the body.